Literary analysis is a formal method of examining a written work to understand how its specific elements, such as structure, language, imagery, and narrative voice, contribute to its overall meaning. It’s the act of reading between the lines and then diving straight through them.

Here’s what to do:

- Read closely and notice patterns, tone, and language

- Identify how literary devices shape meaning

- Write a clear thesis about the author’s purpose

- Support your point with direct textual evidence

- Organize your ideas logically

- Explain your analysis clearly in each paragraph

This article walks you through how to write a literary analysis essay from start to finish with real steps and strategies.

And if you’re stuck mid-draft or don’t even know where to begin, EssayService is the perfect place that students turn to when their ideas need structure and their paragraphs - sharpening.

What Is Literary Analysis?

A literary analysis is a close look at how a story, poem, or play creates meaning. It looks closely at the details: a strange image, a shift in tone, a sentence that feels heavier than the rest. These essays don’t retell the plot, but pay attention to the author’s choices, the structure, character writing, and the language used.

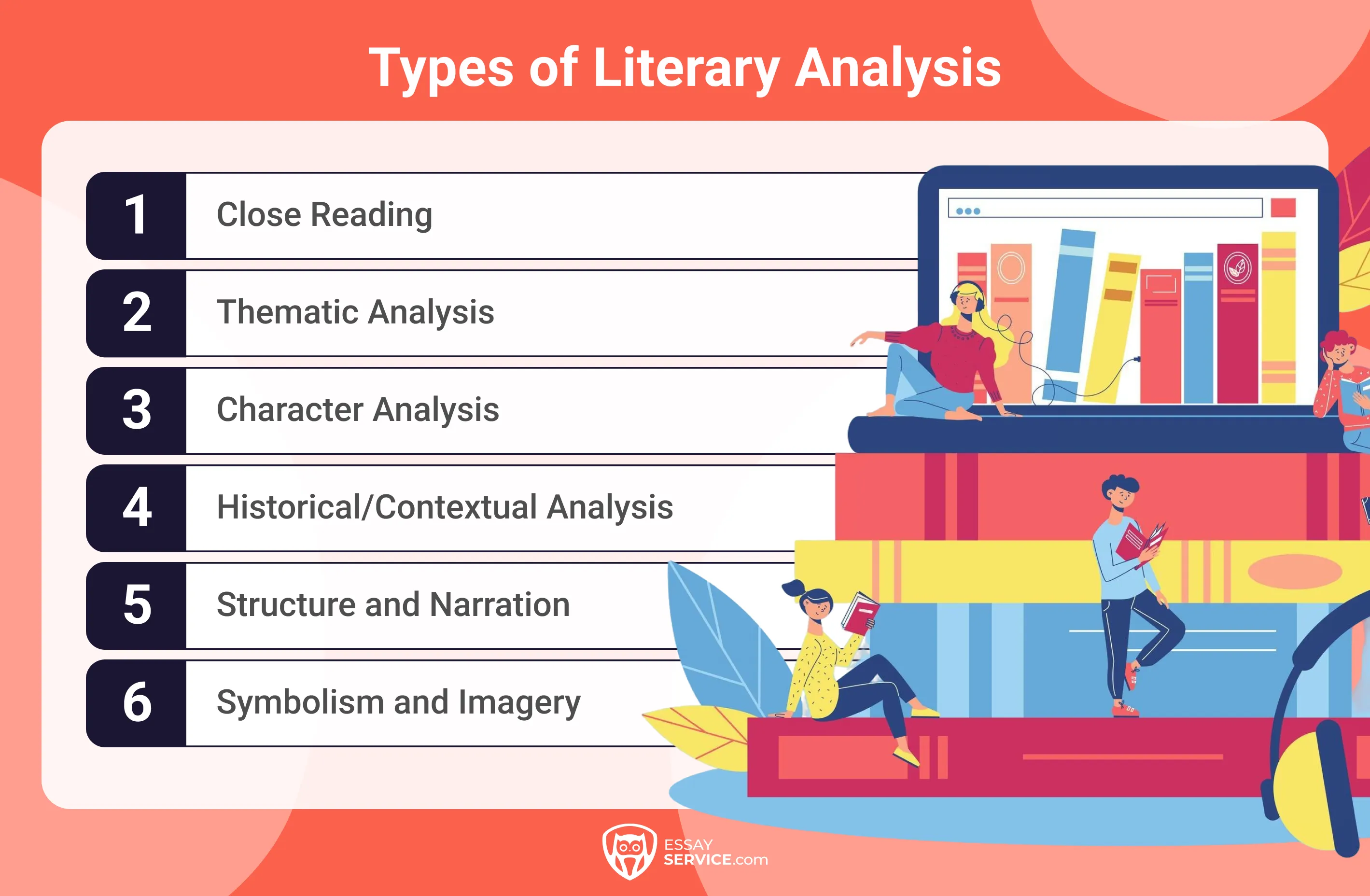

Types of Literary Analysis

There’s more than one way to look at a story. That’s where different types of literary analysis come in. They help you decide what to focus on so your essay doesn’t just float around with vague thoughts.

Here are a few directions you can take:

- Close reading: This is where you slow down. You look at the exact words on the page, how a sentence is shaped, why one image repeats, and what a strange phrase might be doing there.

- Thematic analysis: If something keeps coming up, grief, memory, or guilt, it’s probably worth tracking. This kind of analysis connects those dots to see what the story is really about.

- Character analysis: Instead of treating a character like a plot tool, this focuses on who they are, how they change, what they want, and what that says about the story.

- Historical/contextual analysis: Here, you read with the outside world in mind. The author’s life, the politics of the time, and even the setting.

- Structure and narration: You ask: who’s telling the story, and how? What gets revealed late? What’s missing? That silence often speaks volumes.

- Symbolism and imagery: Sometimes a tree is just a tree. But if it shows up in every chapter, it might mean something more. This kind of reading listens for patterns.

Different essays call for different lenses. If you're focusing on a character's growth or contradictions, a character analysis essay might give you the structure you need.

What Does a Literary Analysis Include?

A good literary analysis doesn’t try to cover everything. It picks a direction and follows it closely, showing how the author’s choices shape meaning. You’re not just pointing out techniques. You’re explaining why they matter and how they work together.

Here’s what to include:

- A clear thesis that makes a focused point

- An introduction that sets up your angle

- Close analysis of specific elements like tone, imagery, or structure

- Direct quotes or passages as evidence

- Well-structured paragraphs that each builds on one idea

- Topic sentences that guide the reader through your points

- A conclusion that opens up the bigger picture

Literary Analysis Essay Outline

Before you write anything, you need to know what you’re trying to say and how you’re going to say it. That’s where the literary analysis essay format comes in. A good outline gives your essay a shape you can build on.

Here’s the structure most strong literary analysis essays follow, whether the writing sounds quiet and thoughtful or sharp and direct:

I. Introduction

- Opening sentence or brief context

- The author’s full name and the title of the work

- Genre (novel, poem, play, etc.)

- Thesis statement (clear, specific, arguable)

II. Body Paragraph 1

- Topic sentence (main idea of the paragraph)

- Textual evidence (quote or specific moment)

- Analysis and explanation of the evidence

- Connection to the thesis

III. Body Paragraph 2

- Topic sentence

- Textual evidence

- Analysis and interpretation

- Connection to the thesis

IV. Body Paragraph 3 (optional or as needed)

- Topic sentence

- Textual evidence

- Deep analysis

- Link to thesis and larger theme

V. Conclusion

- Restate the thesis in new words

- Reflect on the significance of the argument

- Closing thought or insight that leaves an impression

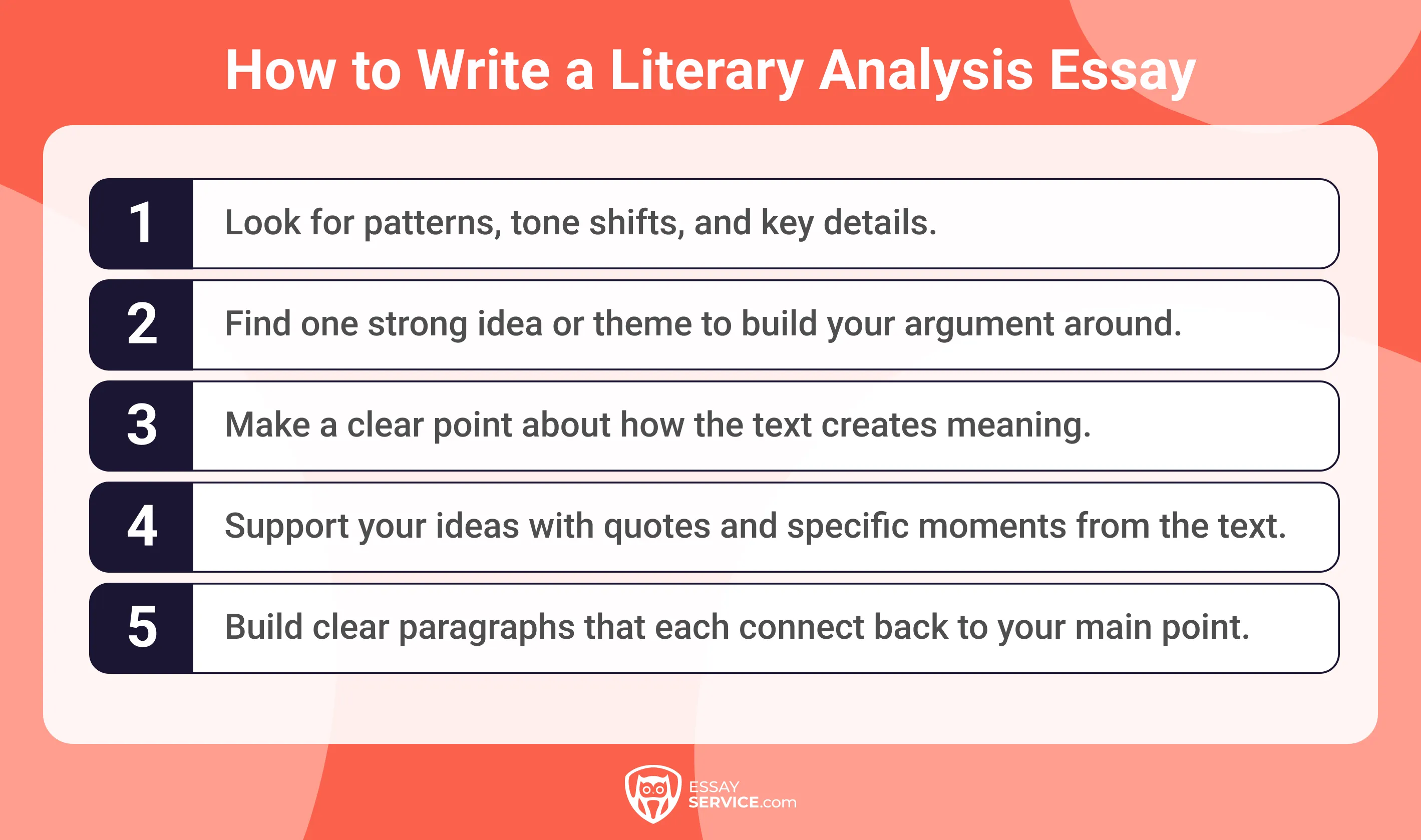

How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay

Some texts stay with you. You finish the last page, and something about it lingers, like an image, a question, a feeling you can’t quite name but it’s there. That usually makes a good literary analysis. Not like a checklist or written by a formula.

If you’ve ever reread a paragraph just to figure out why it hit you so hard, you’re already halfway there. Writing a literary analysis essay just means turning that instinct into a strong argument.

Read Like You’re Not in a Hurry

You can’t analyze a text you haven’t really met. That means you have to slow down, not because you’re trying to ‘catch’ something, but because most authors leave hints in unexpected places. That weird line on page three is probably what matters more than you might think.

As you read, notice the small things that feel loaded. A repeated color. A sentence that doesn’t quite match the mood. A pause where something could’ve been said but wasn’t. You’re trying to understand how literary devices shape greater meaning.

Things worth noting:

- Unexpected word choices that shift the tone

- Images or symbols that return more than once

- Contradictions in character behavior

- Moments that seem too quiet or too loud for what’s happening

- Themes that start to build in the background

What Language Is Trying to Tell You

Writers choose their words like painters choose their colors. Some scenes feel soft because the sentences are gentle. Others snap because every word lands hard. That’s not a coincidence. Language builds atmosphere. It carries emotion. It hides things in plain sight.

When you’re creating your essay, don’t just ask what the author said. Ask how they said it. Look closely at the tone of a sentence or the rhythm of a passage. See what happens when a metaphor shows up where you weren’t expecting one.

You might find:

- Words that echo across scenes, even if the context shifts

- Metaphors that change the way we see a character or setting

- Phrases that feel out of place in a way that nags at you

- Language that speeds up or slows down the pacing of a scene

- A shift in tone that makes you wonder if something deeper is going on

Narrative Voice

The narrator shapes what we see, how we feel about it, and what gets left unsaid. Voice is a power. It tells us where we’re standing and what we’re allowed to know.

Think about who’s telling the story, and what limits their view; whether we trust them or start to question them; how close or distant the voice feels; what details they focus on, and what they ignore.

A calm narrator can make chaos feel normal. A nervous one can make everything feel like a threat. Pay attention to who’s talking.

Structure

Structure is how the story holds itself together or doesn’t. It decides what hits you first, what gets held back, and where the emotional weight lands.

Watch for:

- Whether the story moves in order or jumps around

- What gets repeated, and what gets skipped

- Where the turning points fall

- How the pacing shifts, what’s rushed, what lingers

If your analysis is built around language, structure, and persuasion, you might be writing a rhetorical analysis essay, where the focus is on how the author convinces the reader.

Find the Center: Your Thesis

Once you’ve finished reading and identified some threads that tugged at you, it’s time you ask the most important question: What is this text doing, why and how is it doing it? And that here is your thesis.

To build your thesis, ask yourself:

- What patterns or techniques stood out the most

- How those techniques relate to a bigger idea, emotion, or conflict

- What you think the text is trying to say beneath the surface

Example:

In The Yellow Wallpaper, Charlotte Perkins Gilman doesn’t just show a woman stuck in a room. The woman shows how being told to stay quiet and still can break something inside you. The physical confinement is real, but it’s the silence, the being dismissed and ignored, that really pulls her apart.

That’s specific. It names a technique (confinement), links it to a deeper idea (silence and mental health), and gives you something to build on.

For essays that focus more on cause and effect within a story or event, a causal analysis essay might be the better fit.

Gathering Textual Evidence

Your thesis is only as strong as the support behind it. You can’t just tell us what a story is doing, you have to show us where. This is where textual evidence comes in. You don’t need a dozen quotes. You need the right ones. Look for moments that feel layered, charged, or quietly unsettling. Then break them open.

What to look for:

- A line of dialogue that reveals more than the speaker intends

- A description that reflects a character’s internal state

- A repeated image or symbol with a clear emotional shift

- A turn of phrase that alters how we see a scene

When you pull a quote, don’t let it just sit there. Walk the reader through it. Show them what you see in it and how it connects to the argument you’re building.

In assignments like a poem analysis essay, where every word carries weight, the way you choose and interpret quotes matters even more.

Write Your Title and Introduction

Start by thinking about tone. Are you writing about something eerie? Quiet? Violent? Your title and first few lines should match that mood. They don’t have to give away the whole essay, but they should show you’re paying attention.

Title

Avoid titles that restate the assignment ('A Literary Analysis of...'). You can do better than that. A good title gestures toward your focus without giving the whole thing away. It can hint at the theme, borrow a phrase from the text, or raise a quiet question.

Examples:

'Paper Walls and Locked Doors: Power and Silence in The Yellow Wallpaper'

'Something That Bites Back: Control and Chaos in Lord of the Flies'

'More Than a Ghost Story: Memory and Grief in Beloved'

Introduction

Your title and first few lines are like a door cracked open. Keep it clear. Keep it honest. Then work your way toward your thesis. Build naturally. Let the reader feel how you got there.

What to include:

- A sentence or two of context: author, title, genre, etc.

- Something specific from the text that connects to your focus

- Your thesis: the argument you're going to prove

Example thesis in context:

In The Yellow Wallpaper, Charlotte Perkins Gilman uses the narrator’s slow descent into obsession to show how forced passivity can unravel a person’s sense of self. The creeping wallpaper, the locked doors, the absence of real conversation, all of it points to a deeper kind of confinement that’s harder to see and easier to ignore.

Write the Body of the Essay

This is the part where you stop circling your ideas and start landing them. Each paragraph is a space to say one thing clearly and say it well. You’ve already built your argument in your head, now you’re just laying it out, piece by piece. Keep it focused and don’t overreach.

Paragraph Structure

There’s no magic formula, but good paragraphs do have a rhythm. First, you say what the paragraph is about. Then you show and explain it. Then you bring it back to your larger idea so it doesn’t just float off on its own.

It helps to think like this:

- Start with a sentence that clearly points to your main idea

- Pull in a quote or moment from the text, something specific, not vague

- Unpack it. Why does that line matter? What’s beneath the surface?

- Close the paragraph by looping it back to your thesis

- And don’t rush it.

Example:

If your essay discusses how Holden Caulfield isolates himself because he’s afraid of being seen, you might observe the scene with Mr. Spencer:

Holden’s discomfort with Mr. Spencer’s concern shows how deeply he resists genuine connection.

Then bring in a quote, maybe something he says under his breath, and explain what it reveals about the way Holden sees the world.

Topic Sentences

Your topic sentence is a doorway. With it, you invite the reader into your thoughts and explain what kind of the room they’re entering into. So, it needs to connect to the rest of the house. If your paragraph starts with a summary or a vague opinion, the reader won’t know where they are.

A strong topic sentence:

- Makes a specific claim

- Sets the focus for the paragraph

- Links clearly back to your thesis

If your thesis is about silence as a form of control in The Yellow Wallpaper, a topic sentence could be:

- The narrator’s fixation on the wallpaper grows louder the longer she’s ignored.

- It’s clear, it sets up your evidence, and it keeps the argument moving forward.

Using Textual Evidence

Quoting the text means showing the reader where your insight is coming from, what you saw, exactly, and where you saw it. In what certain way did that make you feel? It should feel natural, not forced. Like pointing something out to a friend: See this? This is where it clicks.

Here’s how to make your quotes do real work:

- Choose lines that feel layered, ones that say more than what’s on the surface

- Set them up so we know where we are in the story

- Don’t just drop the quote. Walk us through it. What’s it doing? What’s the tone?

- Tie it back to your point before you move on

Example:

If you’re writing about fear in Lord of the Flies, you might bring in the line, ‘Maybe there is a beast... maybe it’s only us.’

Don’t just leave it there. Take it apart. What does it mean that the boys are starting to fear themselves more than the outside world? How does that shift the entire story? That’s where the real analysis lives.

Write the Conclusion

Don’t just recap everything you’ve said in your last paragraph. It’s your moment to step back and show the reader the full picture. You’ve walked us through your thinking. Now, what does it all add up to? What do we see now that we didn’t at the start?

You don’t need to say something grand. You just need to say something true. A quiet, subtle final sentence can stay with the reader longer than a dramatic one.

Literary Analysis Essay Example

Below is an example of a literary analysis essay written about The Passion According to G.H. by Clarice Lispector. It takes a close look at how Lispector uses silence, structure, and isolation to dismantle identity and confront the rawest parts of being human.

If your assignment leans more toward interpretation or judgment, check out our critical analysis essay that might be exactly what you're looking for.

The Final Line

The true essence of literature is noticing little things and trying to make sense of them. The same goes for analysis. Here’s what to carry with you:

- Stay close to the text. The answers are usually right there.

- A good thesis covers one specific idea clearly.

- Don’t retell the story. Show us how the author made it work.

- Little things like voice, structure, and words are never just little.

- When you quote, don’t just drop it in. Walk us through why it matters.

- Keep your paragraphs focused. One idea at a time. One moment at a time.

If literature analysis isn’t your strongest suit, or you just need a second pair of eyes, EssayService has got your back. Our writers will dive deep into literature and come back with unique insights and a fascinating use of language.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is a Literary Analysis Essay?

Literary analysis essay is a type of writing that goes beyond a story and focuses on how it was built. You’re breaking apart whatever stands out, such as the structure, the voice, the language, and the symbols.

How Long Should a Literary Analysis Essay Be?

Most school or college assignments ask for something between 600 and 1200 words.

How to Start a Literary Analysis Essay?

Find one moment that stands out. Ask why it matters. A strange sentence. A pattern that keeps showing up. A detail that feels too quiet to be random.

Jennifer is a student currently pursuing a Journalism major. She oversees the EssayService blog team and uses her journalism skills to ensure all blog posts are accurate, trustworthy, and engaging.

Writing Center, University of Wisconsin–Madison. (n.d.). Close reading. https://writing.wisc.edu/handbook/closereading/

New posts to your inbox

Your submission has been received!